|

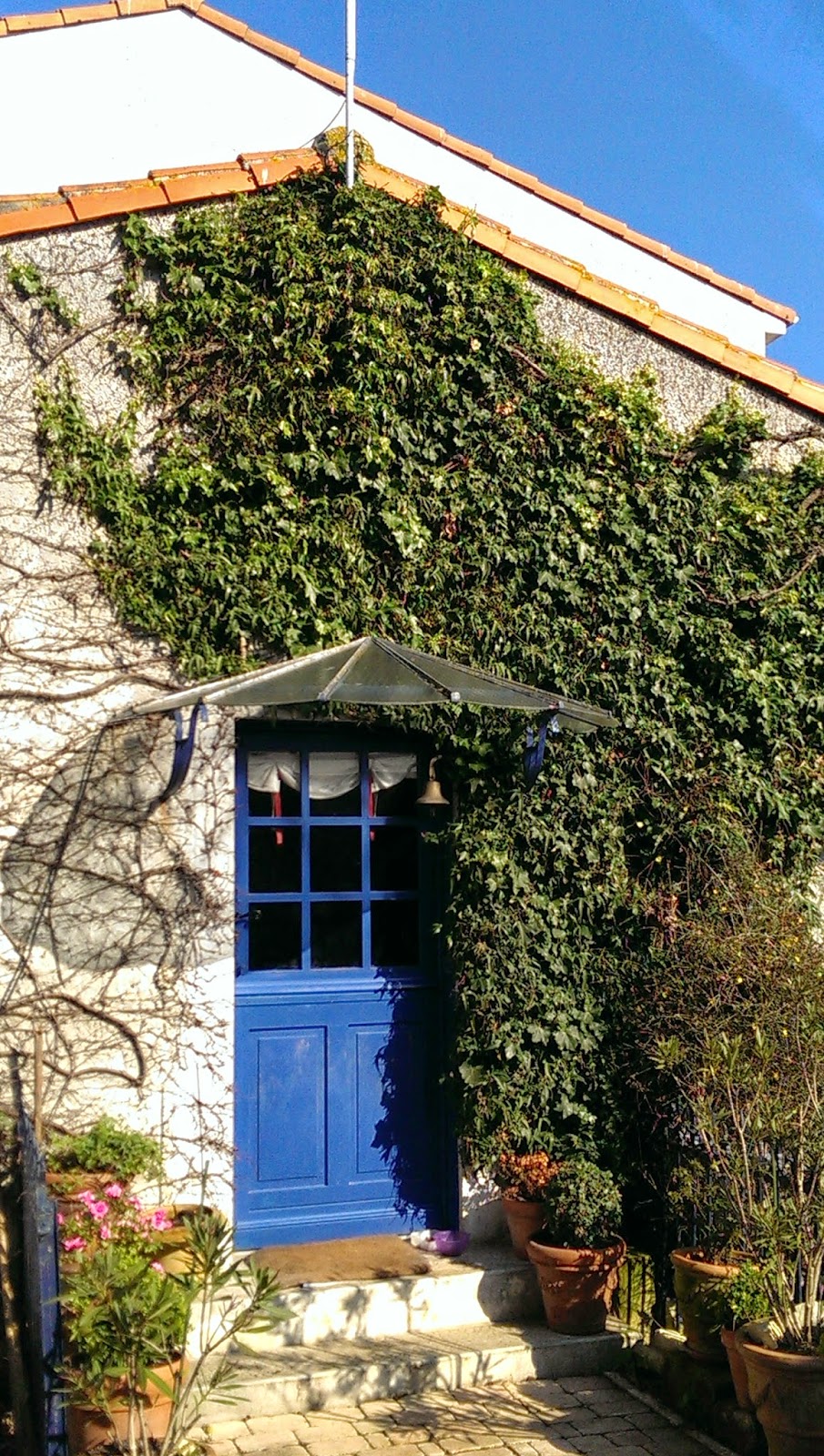

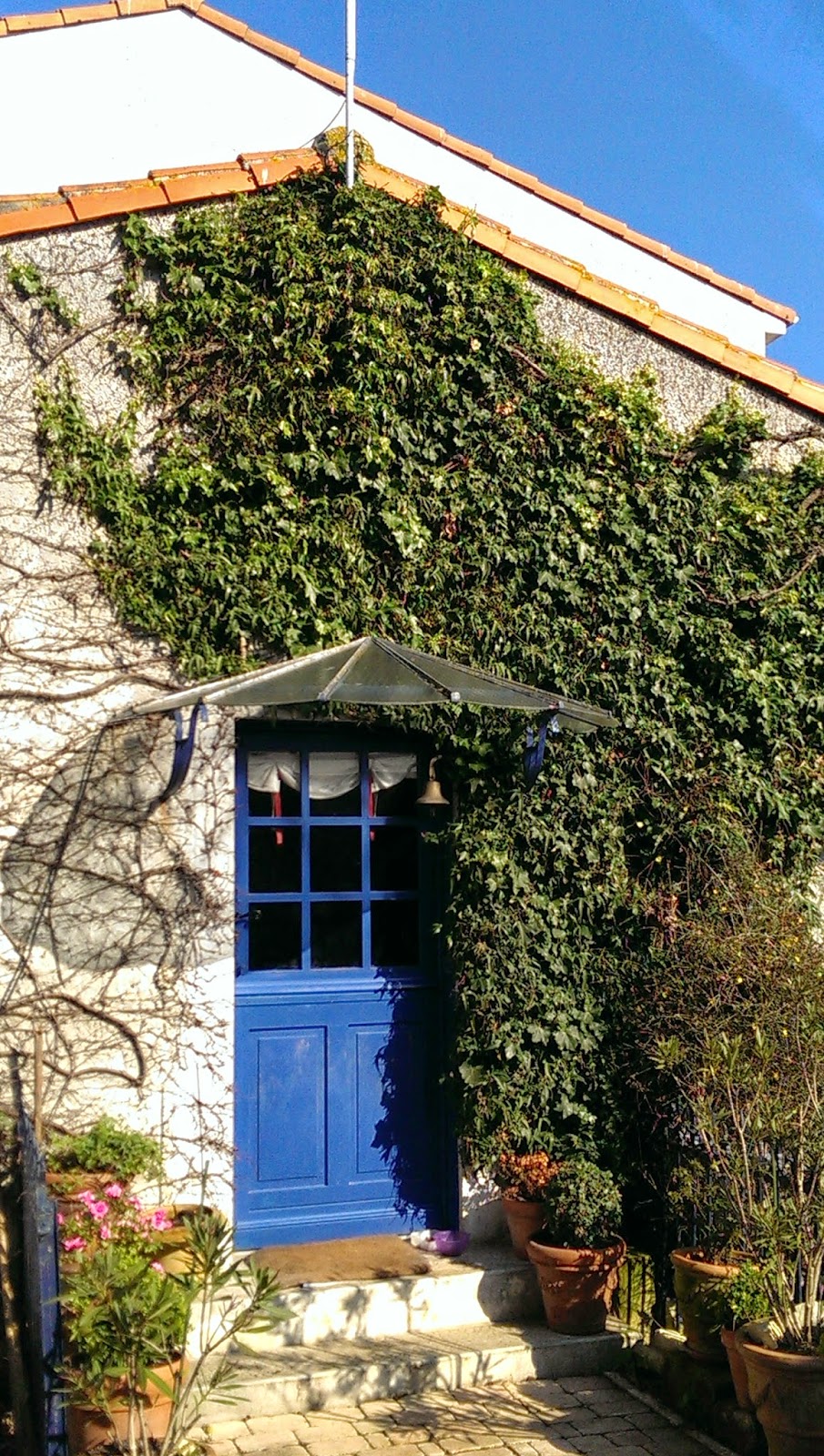

The garden door chez

Phillip and Patricia |

Phillip, who is a business professor at the University of La

Rochelle, does not have classes on Monday and thus was free to spend most of the

day with us—after he took Sinclair to campus for

his first class at 8:30, and attended a faculty meeting. While he

was gone, the rest of us enjoyed a leisurely continental breakfast. After that,

Michael and Nancy started their Monday-morning laundry while Patricia finished

putting together a

tarte aux pommes

(apple tart) to be served at lunchtime.

At this point, we would like to make it clear that although

we offered to help Patricia prepare meals and clean up afterward, she would accept

no assistance, explaining that it was easier for her to work alone in her

culinary atelier than to direct people who didn’t know where anything was and weren’t

familiar with her methods. We understood completely—and we certainly didn’t

want to hinder her ability to continue producing such marvelous meals.

Between loads of laundry, we took time to work on our blog. Patricia

probably would have been offended by the fact that our attention was directed

toward our digital devices rather than toward other human beings, had she not

become intrigued by our

modus operandi.

Having been raised by an aristocratic grandmother who presided over a very

traditional French household, Patricia has tried to cultivate the genteel ambiance

of an earlier era in her own home by eschewing some of the more vulgar

trappings of our modern age; to wit, she does not use an electric food

processor, a microwave oven, or a computer. Writing with anything other than pen

on paper is a foreign concept to her, as is assembling a photo album without

glue or adhesive corner mounts. So she was fascinated as she watched us work

back and forth among our devices, especially with the fact that words appeared

on Michael’s tablet as he typed, even though his Bluetooth keyboard isn’t physically

connected to it. Patricia was concerned that by focusing on our screens we were

isolating ourselves from real human contact, but her fears were allayed

somewhat when we explained that even though it seems that we are working

separately, we really have to coordinate our efforts: Michael usually writes

the first draft of each blog post, which Nancy then edits after incorporating a

lot of her own material. In the process of creating the narrative, we ask each

other a lot of questions to verify details and make sure we haven’t left out anything

significant. Michael usually decides where to insert the photos and tries to appropriately

format the surrounding text (although Blogger can be annoyingly uncooperative

with that task), and then Nancy checks to make sure the photos are in the right

places and the captions are accurate. Patricia finally seemed to understand that

the process requires a lot of interaction and cooperation, and when she

realized that we were creating the blog in order to share as many of our travel

experiences as we could with far-flung family and friends, she appreciated the

fact that our digital devices allow us to do that almost instantly—once the

writing and formatting are done.

|

| Le table Harvard |

While we continued alternating between writing and folding

laundry, Patricia prepared lunch. Our first course, served in cocktail glasses,

consisted of cubes of something she called—for lack of a better English term—“bread

meatloaf” (a sort of savory bread pudding), topped with a creamy cucumber-sorrel

sauce, and decorated with leftover shrimp. (Isn’t it amazing what delicious

concoctions a creative cook can devise with whatever happens to be at hand?)

The main course included delectable twice-cooked duck thighs and potato purées

in two different colors: one golden, the other purple, made from

vitelotte potatoes. The

vitelottes definitely had a musky, more

earthy taste than the golden ones. We

finished with the requisite salad and cheeses, and an excellent

tarte aux pommes. When we asked Patricia

whether she served multicourse lunches only when she had guests, or if she

prepared something so elaborate every day, she laughed off our term “elaborate”

and said, “At least three courses, twice a day, every day. That is our custom.”

|

Painting by Jacqueline Nesson

(otherwise known as "Mamina") |

Soon after lunch, we dropped off Patricia’s 92-year-old

mother at l’Houmeau’s equivalent of a senior center so she could attend her

painting club. (Mamina is an accomplished artist and equestrienne who specializes

in portraits of horses and dogs.) The two couples then drove about forty

kilometers across the marshes to the Château de la Roche Courbon. The original

castle, which had been built in the fifteenth century on a rocky promontory

rising from the wetlands, was transformed into an elegant residence during the

seventeenth century by Jean-Louis de Courbon. The marquis refused to flee during

the

French Revolution and the family was allowed to

continue occupying the estate, but when upkeep became difficult the château

fell into disrepair and eventually was abandoned. In 1920, it was purchased by

Paul Chénereau, who restored the château and its gardens. This was more

complicated than one might initially imagine because the grounds had been completely

inundated by the River Bruant, which runs through the middle of the property.

|

| Entering the Chateau de la Roche Courbon |

In

order to restore the gardens to their former glory, Chénereau brought in an

engineer to design a gigantic raised bed in which grass, flowers, and

ornamental shrubs grow, while water continues to trickle underneath. The river constantly

replenishes a large reflecting pool as well as the fountain that flows from an

impressive staircase opposite the château. The property also includes some

prehistoric cave dwellings, which our children had enjoyed exploring when we

visited in 1993. Chénereau’s descendants retain one wing of the Château de la

Roche Courbon as a private residence, even though most of the estate is open to

the public. It has been a favorite place for Phillip and Patricia’s family to

visit through the years, and now has become particularly dear because it is

where Astrid and Geoffrey held their wedding celebration. (We were delighted to

discover a large photo of that grand event on display in the castle’s museum.)

|

| Chateau de la Roche Courbon |

|

| The gardens at the chateau grow in what amounts to a giant raised bed to keep them above the marshy ground |

|

| Phillip and Michael atop the stairway (the fountain wasn't flowing today) |

|

| View from the chateau''s ramparts |

|

| Michael and Nancy at the Chateau de la Roche Courbon |

|

| La Rochelle's Harbor |

On the way home, since Michael had a craving for some of the

gelato he had seen yesterday while we were strolling around La Rochelle, we

drove downtown again.

Mais malheurs!—the

gelato emporium was closed. We settled for another round of

chocolate viennoise and

citron chaud,

this time at the splendid Grande Époque-era Café de la Paix at the

Place de Verdun, near the Cathedrale Saint Louis de la Rochelle.

|

| Cafe de la Paix |

Later, while Patricia prepared dinner, Michael drove Phillip

back to the university to pick up Sinclair.

Since they arrived a few minutes early, Phillip showed Michael his office

at the business school, which is across the street from Sinclair’s undergraduate

school.

Another “simple” meal—leek and potato soup, salmon omelet, salad,

and pastries—was ready when the men came home.

Although topics for previous

mealtime conversations have been all over the map, tonight we focused on

Sinclair and his studies. He is in his third and last year of an undergraduate law

program, and then will go on to a two-year graduate course leading to a law degree.

We were very interested in his description of recent changes in the French

university system, made at the behest of other universities in the E.U. to

bring about more commonality among their degree programs, and to foster educational

exchanges across the continent. He told us that all European universities now

use a sixteen-week semester schedule, similar to the standard U.S. model. Also

borrowing heavily from the American system, uniform values for “credits” have

been established; but whereas U.S. credits generally correspond to the number

of hours spent each week in the classroom, credits in the E.U. reflect study

time as well as classroom time. Study hours are arranged—and controlled—by the

university; so when Sinclair says he is taking a thirty-hour load, what he

means is that he is at school—either attending class or studying—thirty hours

each week. Credited time includes formal lectures, large-group “sections” or

labs, as well as small-group study sessions. Another major difference from the

American system is that rather than handing out a syllabus of required readings

and expecting students to study them on their own, professors provide all

necessary information during class time, taking questions and explaining as

they go along. Thus students here don’t really have what we think of as “homework,”

but they do have regular exams and other assessments so teachers can evaluate

their progress and make sure they understand the course material.

This dinnertime discussion interested us not only because of

the topic, but because it gave us the opportunity to hear Sinclair express

himself in English. Of Phillip’s three children, Sinclair is the most quiet and

reserved, and he has had the most difficult time mastering his father’s native

language (which the family has always tried to use at home). The last time we

had seen Sinclair, about four years ago during his first visit to the U.S., he

spoke very little—but listened and observed attentively. Even now, he is much slower

to enter the fray of dinner conversation than the rest of his family (much like

Nancy, who usually feels the need for so much mental editing before she says

anything that she often just stays silent while others let fly). Tonight,

however, without older siblings around to dominate the discussion, Sinclair

spoke fluently and with confidence in his second language, and we very much

enjoyed learning from him.

No comments:

Post a Comment